|

| Climbers on Rainier's crater rim. |

The pulse began with a rescue in the adjacent Tatoosh Range, a rescue I was recruited into with Eitan Green. Less than four weeks after that successful rescue effort an unfruitful rescue was, in turn, underway for Eitan and the other five members of the party swept 3000' down the flanks of Liberty Ridge.

Twenty-four hours earlier I'd pulled into Ashford, after pulling the plug on a Mt. Hood ski ascent/descent, waiting for better weather. Bluebird skies did arrive and my partner Jared and I headed out for a ski tour in the Tatoosh. Ignored by many, the subsidiary Tatoosh offers spectacular stadium seating on the Muir Snowfield leading up to Rainier's Disappointment Cleaver Route, the most popular avenue to Rainier's summit cone. Eitan and I passed many a high five on the up-down of that path. Occasionally, we shared some time together in the valley. I'll always remember his smile.

Far and away though, the longest time we shared was that eight hours on the rescue. It was a fitting place to share with him—given Eitan's caring way of being. At the end of that late day I remember thinking to myself that he was a fellow I would want to expedition with in the future—the sweetness of it all embittered now only by his death.

Wrapping up our morning of touring, Jared & I encountered Eitan, along with his girlfriend and another ski partner around noon. They were looking to launch their own tour, but had it cut short by a bloodied woman, her partner stranded in the choke point of the Fly and Zipper Couloirs on Lane Peak, swept by a collapsed cornice fall as they ascended. It was still early season, the sun was strong, and cornices were weak. Allayed from his planned day with friends touring the Tatoosh backcountry, he seemed characteristically at-ease, good-natured about it, and committed to doing what needed being done. He recruited us and we all skinned off through the glades toward Lane Peak with some Park Service personnel in tow. We found the climber conscious, cut up, broken, in descent shape, but certainly not in a condition to walk out, and given the terrain, a sled/litter rescue was going to take a long time. As it was, it wasn't until sunset that the fellow flew off, short-lined underneath on MD-500 helicopter. By then the snow was a bit thick for easy turns, but we made the most of it in the dying light, even tackling the last few steeps by headlamp, to land us right back at Eitan's truck. That was the last time I saw him.

|

| Evacuation of the injured climber on Lane Peak. |

|

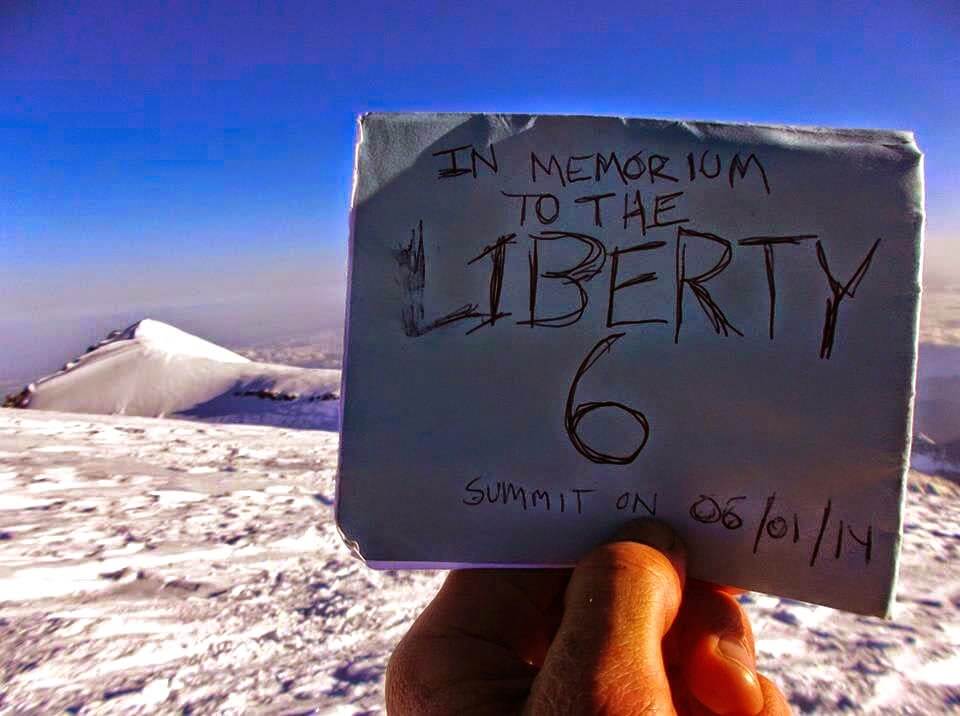

| A summit of Rainier on the day the fate of the Liberty 6 became clear. |

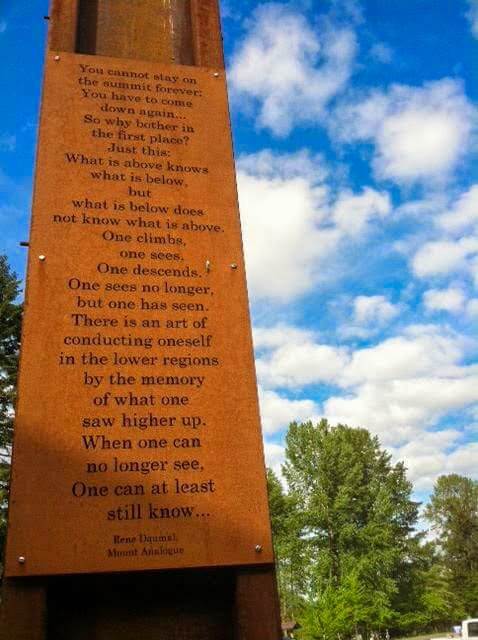

In any case, dealing with this caused me a appropriate amount of reflection on what it is that I do—and more importantly on why I do it. I've arrived at a point no consequentially different from where I began, but such is the nature of climbing—the person has changed nonetheless. In an eerie strike of coincidence, 2 days before the death of the Liberty 6, I'd posted a photo of a plaque at the RMI Basecamp. It's a quote from adventurer/writer Rene Daumal exploring the question of why we climb:

"You cannot stay on the summit forever; you have to come down again. So why bother in the first place? Just this: What is above knows what is below, but what is below does not know what is above. One climbs, one sees. One descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen. There is an art of conducting oneself in the lower regions by the memory of what one saw higher up. When one can no longer see, one can at least still know."

"You cannot stay on the summit forever; you have to come down again. So why bother in the first place? Just this: What is above knows what is below, but what is below does not know what is above. One climbs, one sees. One descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen. There is an art of conducting oneself in the lower regions by the memory of what one saw higher up. When one can no longer see, one can at least still know."

|

| The Daumal quote at RMI Basecamp. |

The reasons for climbing are as myriad as climbers themselves, and perhaps even among climbers it changes with the route, the situation, and the stage in life. You can be quite sure that some of those reasons are half-baked. But even the half-baked ideas are half-cooked and among all the half-cooked portions there is likely a similar shared distaste for apathy, for ambivalence, and dispassion. Aside from the death of a friend and a colleague, what have I seen to show for this season?

|

| Descent from my final Rainier summit of the season. |

-

A sixteen year-old kid from Singapore. He was quiet; we didn't converse much, hardly even made eye contact really. He'd flown all the way over with his Pops. Celebrating our climb at the Basecamp Bar and Grill afterward, the dad got teary-eyed and eloquent—the kid was characteristically quiet. Later I learned that his climb had been a fundraiser for an orphanage in China.

-

Two climbers from a Rainier skills seminar last year, descending the Muir Snowfield. We hadn't been able to summit last year, but they'd taken those skills out for a go on an independent climb this time this season. They looked confident and satisfied, and they had a summit to show for it.

-

A fitness trainer from Corpus Cristi, Texas. Despite his obvious athleticism, the preparation he'd undertaken in the flatlands of Texas hadn't prepared him for Rainier. On our summit day, he stayed at Muir. I can only imagine the challenges I'd have in taking such a thing with equanimity were I in his place. But that's like thinking that because I climb Rainier a few times week I'd be ready for a 2 mile swim or a powerlifting competition....or saxophone solo for that matter. He's approached it with resolve and spirit—in fact, I'll see him this autumn for some alpine and rock climbing training in New Hampshire.

-

Eric Carter at 13, 500 making his last strides toward the summit cone, bedecked in lycra, light-weight randonee ski boots and little else. We had hardly begun the descent of the Cleaver at 12, 200' when he rattled by on the slick 45 degree no-fall zone alongside our path, edges chattering, barely connecting with early-morning ice crust. It seemed we'd only descended another 100' or so when I saw him poling full-force nearly 1000' feet below across Ingraham Flats. His time of 3 hours and 51 minutes now stands as the Rainier record.

-

Old friends reconnect via a climb. Learning the “who-was-who-and-how-they-were-related” in this tribe of ten felt a bit like reading John Krakauer's “Under the Banner of Heaven.” Unlike Krakauer's novel, not all were, but they shared a common sense of enthusiasm. In the face of grim forecast we left Camp Muir, pushing forward, but had to call it quits at The Flats. Despite the lack of a summit, we achieved the objective and friends, brothers, college roommates, brothers-in-law, and whatever-else shared the joy of energy toward a common objective.

There it is—a small glimpse of the many minor and major moments that occur when people bring their hearts and minds toward accomplishing a large objective.

Beyond the mountain, there were also many shared meals, conversations, and laughs at the guide ranch. Laughs and conversations dimmed for a time in early June as we each pondered the sudden fate of the Liberty 6, our own fragile and ephemeral existence, the timelessness of the mountains, and what calls us toward them. I don't know the end point to which each has arrived, but in some small and largely inexplicable way I understand where I stand and where I strive toward, and I will climb on.

|

| "One descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen..." |

Adventure Spirit Rock+Ice+Alpine Experiences

AMGA Certified Rock+Alpine Guide

No comments:

Post a Comment