|

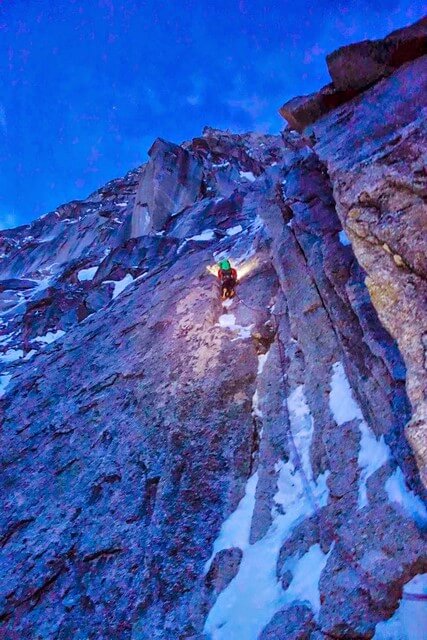

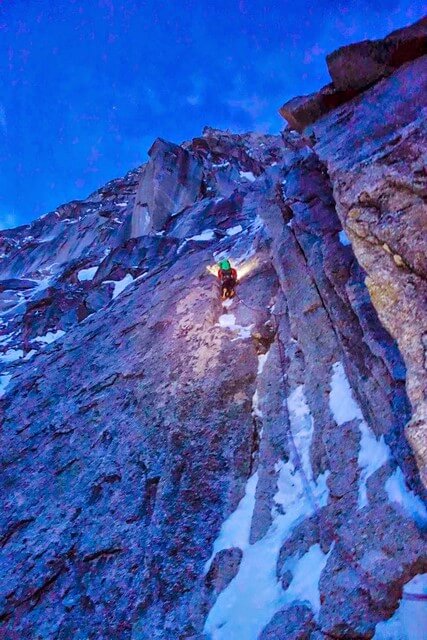

Approaching the North Buttress of Begguya (Mt. Hunter)

©Doug Shepherd |

Climbing with three has it's appeals. Splitting the work with an extra person, more warmth while cuddling, and general camaraderie. That said, I've been known to repeatedly say "I hate climbing in the mountains with three" and turn down climbing trips, especially on technical alpine routes. My reasoning for this comes from many failed climbs with three people, due to general slowness, stuck ropes, difficult communication, and even a lack of stoke!

However, I've recently had a break-through, efficiently climbing large routes with a team of three. Part of this is finding the right partners and part of it is due to finally figuring out the right gear and tactics for efficient movement with three people. Keep reading for my take on making it work in the mountains with three.

My main issue with three has been speed. I felt like the climbing went slower, even though we had more people to split the work with. Looking back, I think one of the reasons was that we had actually gone too light. Stepping back and evaluating the durability of certain key pieces of gear (like ropes) you need for your chosen route and strategy will make a huge difference in everyone's comfort level and speed on the route.

|

Keeping the stoke up is key!

©Doug Shepherd |

In early spring this year, I was kicking around the idea of a big mountain day on Longs Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park with my friends Scott Bennett and Chris Sheridan. We finally decided on going for an ascent of the Dunn-Westbay, recently the site of a free climbing push by Pete Takeda, Josh Wharton, Tommy Caldwell, and others. Given the time of year and freezing levels, we planned on aid climbing once our ability to free/mixed climb in boots ran out. Because of this, we brought a small stove, two single ropes, a gri-gri, jumars, and alpine aiders.

|

Scott and I racking up below the Diamond

©Chris Sheridan |

After climbing up the lower east face and the first pitch of the route proper with crampons and tools, we switched over to aid climbing mode. At this point, things slowed down as the leader moved their way upwards. At the belay, one second would belay the leader and the other would brew up with our small stove. Because we had two single ropes, the leader could short-fix after setting the belay, allowing on one second to quickly jug the free hanging line and the other second to clean the pitch.

|

Cleaning the pitch after tagging the rack up to the leader

©Chris Sheridan |

The day went smoothly and we topped out of the route shortly after sunset. We then pulled out the most important piece of kit at the top of the route, the celebratory snack and travel pig! I find that keeping the experience fun and humorous is one of the best ways to keep the stoke on long days, which is why I always make room for these ritual items in the pack.

|

Travel pig and peanut butter cups!

©Scott Bennett |

Riding high on this experience, I was kicking around plans for a quick Alaska trip once my semester ended. I collected my students' final exams and headed north the next day with my Chris Sheridan and Phil Wortmann. We were roughly planning on climbing on the North Buttress of Begguya (commonly known as Mt. Hunter), but we were unsure of the exact route or conditions. Because of this, we flew onto the glacier with a huge amount of gear for short 4 day trip.

|

The massive gear pile that we took with us into the Central Alaska Range

©Doug Shepherd |

Two key gear decisions we made dealt with our ropes and puffy jackets. We chose to take a set of thick half ropes, specifically the

Mammut Genesis 8.5mm ropes. I've had a multiple pairs of these ropes over my climbing career and I've never retired one due to rope damage, only because the dry coating had worn off or they were just so old I knew I should get new ones! One of the key properties of the Genesis ropes is the high proportion of sheath, 49%, which is higher than skinny single ropes. For us, this meant higher confidence in simul-seconding and simul-rapping high on a alpine wall.

We all decided to take two puffy jackets, one synthetic (a

Mammut Rime Pro for me) and one down (a

Mammut Broad Peak Hoody for me) jacket each. Because we had decided to climb in a push, it was important for each of us to have dry insulation available for the higher portions of the route, any possible brew breaks, and the long descent. I prefer this system because you have an "active" belay jacket and an "inactive" belay jacket. There are a lot of options here and I prefer the Rime Pro because it fits like a climbing jacket, has a set of deep interior mesh pockets, and a breathable shell on top of synthetic insulation. Having a breathable shell is key, as it allows moisture to pass through the jacket and dry your climbing layers out.

Arriving at Kahiltna basecamp, we arrived to record high temperatures and quickly decided to attempt the Bibler-Klewin route in a push. We napped through the heat of the day, leaving basecamp so that we could climb the lower portion of the wall during the colder hours of the night. As we approached the bergschrund, we noticed a lone climber rappelling the route. It turned out to be my friend Kyle, was descending from a solo attempt at the Bibler-Klewin route.

|

Super stokage with travel pig and Kyle!

©Doug Shepherd |

Feeding off the excitement of seeing Kyle, we charged over the overhanging bergschrund and starting up the lower portion of the route, climbing through the night to watch the sunrise above the Prow pitch.

|

Myself leading us over the bergschrund and into the first long block

©Phil Wortmann |

|

Phil taking us towards the Prow after taking over the leading duties

©Doug Shepherd |

In my experience, leading in blocks is the most efficient way to climb a large route. To speed the process, we intentionally overloaded the seconds' packs to allow the leader to move as quickly as possible on the steep and varied terrain. The seconds then followed simultaneously and cleaned the pitch. To speed the transitions, each climbers keeps some climbing food, their "active" puffy jacket, and a small water bottle in the lid of their pack. The lid then stayed with that climber while we swapped light or heavy packs depending on leader or second.

|

Chris leading Tamara's Traverse

©Phil Wortmann |

We quickly made our way through the picturesque Tamara's Traverse, hooting and hollering the whole way. We kept cruising, taking a brew-up break below the Shaft pitches while a party ahead of us battled with those pitches. We eventually made the decision to cut over to the Twight-Backes route Deprivation, as we had a limited amount of time available and couldn't wait any longer. After a long snow traverse, we found extremely high quality ice and mixed runnels that eventually led us to a ramp system and the third ice band. Reaching the Bibler Come Again exit pitches after hours of simul-climbing, we decided to take our first real break and dig out a site to sleep for a few hours. We brought Chris' custom "alpine blanket" to share between all of us, although Phil eventually decided to dig his own sleeping cave instead of snuggle with Chris and I.

|

The alpine snuggle blanket and "inactive" jackets keeping us warm for our brew stop

©Phil Wortmann |

After a fitful nights sleep, a lot of hot drinks, and a quick meal we set off to finish the exit pitches. It turned out to be perfect ice climbing through the pitches and we quickly found ourselves on the final ice band. The weather was clearly unstable and we had to catch our plane off the glacier the next day, so we decided to rappel instead of finishing the route. We simul-rappeled the whole route, setting our own naked v-threads (where the climbing ropes are directly thread through the ice) the whole way down, leaving one piece of cord to back up an existing anchor on our whole descent.

|

Three happy guys and travel pig on the final ice band before turning around

©Doug Shepherd |

|

Phil and Chris simul-rappeling high on the North Buttress

©Doug Shepherd |

Skiing back into basecamp 48 hours after leaving, we were content with our effort on such a large route with minimal clusters. A huge part of this is the thought and organization that went into our gear choices, our tactics on the route, and the decision to cut around the party ahead of us onto the Twight-Backes route. The best gear choices in the world won't get you up a route, only your skills, training, decision making, and most importantly teamwork will propel you upward when faced with adversity. Having an extra friend along to share the burden can provide a huge boost of motivation and stoke when you are feeling down.

-Doug Shepherd

Denver, CO